On the art of being real

To love is to be vulnerable, to risk suffering and uncertainty. The world promises safety to no one, however much they are loved. And yet we love anyway, because that is who we are. I feel this most acutely now I’m a parent, but I have known it all my life, and I learned it first from Elsie…

When I was two years old, Elsie the toy rabbit went everywhere with me. Her body was soft and brown, except for her long arms and legs which were a silky purple and closer to human than rabbit. I would hold her by her hands and by shifting her weight from side to side, make her legs move as if she were walking. Or she would sit, flopped against me as I recited my storybooks from memory, usually stories about rabbits, a persistent interest for me at that time, “It is said that the effect of eating too much lettuce is soporific.” Beatrix Potter was never one to talk down to children, and that was fine with me. I didn’t need to understand all of it. It was enough to imagine those water-colour rabbits wandering around the countryside, dressed in their old-fashioned clothes, enjoying fancy tea parties in their burrows. I had no doubt real rabbits did all those things. Of course, they did. But only when no-one was watching. It had always seemed to me, from very young, that there were two worlds – The outer world that was obvious to everyone, and the inner world, which never properly matched the outer world and so had to stay hidden.

When I told my father it was Elsie’s birthday, he gave me a cake, put some candles in and lit them. Then he sat down opposite me with his instant coffee and started reading his newspaper. I knew the script for birthdays. I sang to Elsie, then lowered her over the cake so she could blow out her candles… My mother (who is now divorced from my father) still flinches at the next part of the story, “What was he thinking? Why wasn’t he watching you?” I can’t answer that. All I know for sure is he leapt from his seat to protect me from the consequences. Elsie’s face fizzed with steam as it hit the water in the kitchen sink, my wide eyes glimpsing the horror for the briefest of seconds, the charred fur slipping from her cheek, exposing the bruise of red and blue stuffing beneath. My father was quick, swooping across her with a long white bandage, concealing the damage and assuring me she would make a full recovery. It took my mother a few nights to reconstruct Elsie’s face. She couldn’t find any brown fur, so she used black fur instead. This left Elsie with a face that failed to match the rest of her body, and a new bewildered expression, with misshapen eyes, nose, and mouth all fashioned for her out of old scraps of felt. To me she was as perfect as she had ever been.

All this meant for much of my childhood I dragged around a toy rabbit that other children would laugh at. Why are you playing with that ugly old thing? Why does it look like that? I would respond by hanging my head and clutching Elsie closer to me. I was an anxious child and rarely spoke outside my home. Yet at night I would speak to Elsie, whispering into her long ears, telling her how lovely and beautiful she was. Those other children didn’t know her the way I did. They would never understand her, just as they would never understand me.

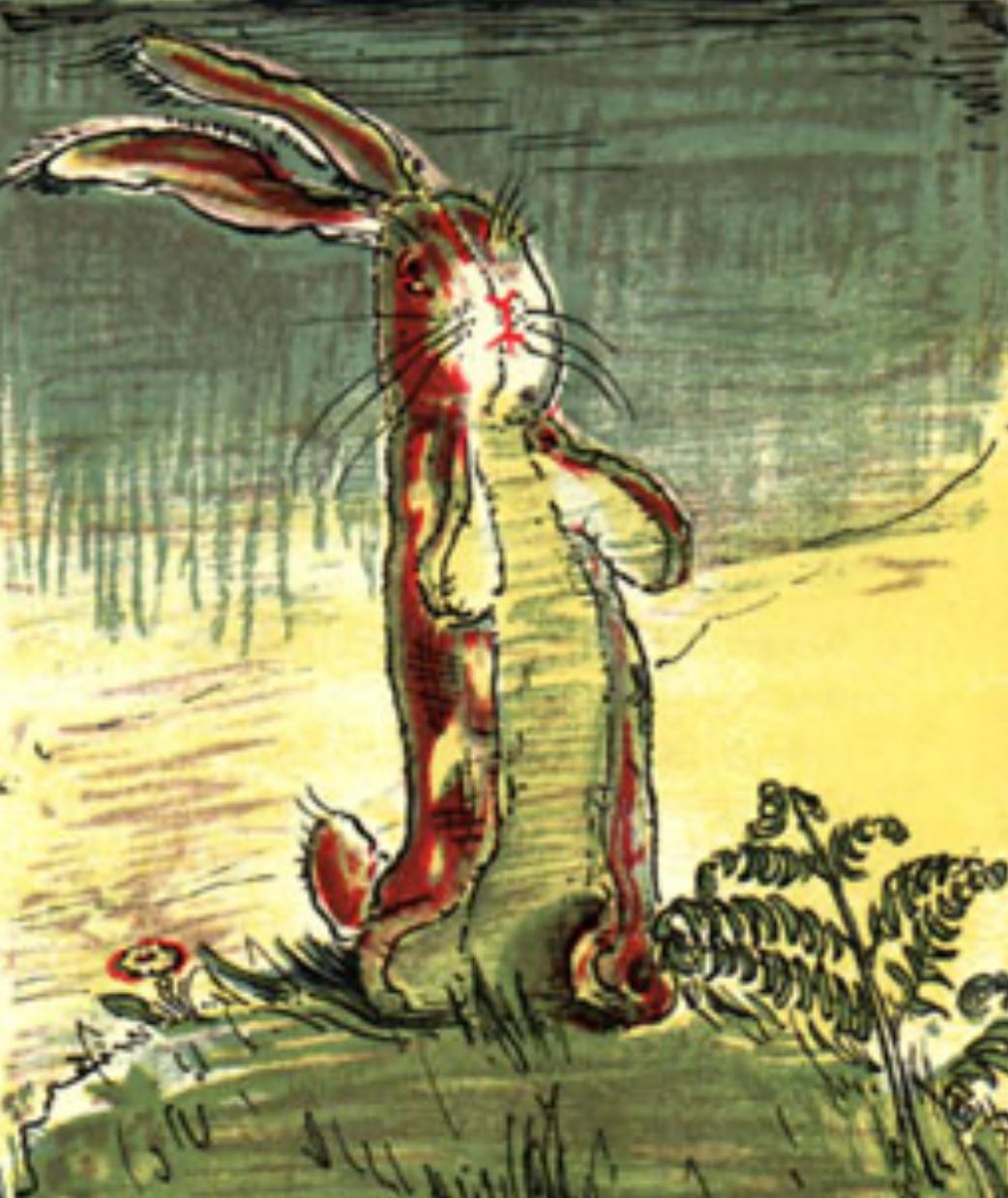

I was around six years old when I was given The Velveteen Rabbit - Margery Williams’ classic story about a toy rabbit, so loved by a child that it is worn out, with bits dropping off it, and through this experience becomes Real, “Generally by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and you get loose in the joints and very shabby.” I can now read this book as a metaphor for the vulnerability we all experience when we let ourselves be known and loved, yet to six-year-old me it was a book about another Elsie and I read it endlessly, “Because when you are Real you can never be ugly, except to those who don’t understand.”

Many years later, I am mother to J, my beautiful autistic boy whose disability is obvious to anyone who sees him struggling to communicate, needing to touch everything in sight, stimming loudly and wildly. I sometimes find myself thinking about that velveteen rabbit, seen by other rabbits as not quite real, as not like them, and I wonder what it is about difference that makes people so uncomfortable?

I witness this discomfort infrequently enough for it to be a jolt, snatching my breath and ejecting me from the moment I was in, yet often enough for it to land me in familiar territory. I recognise the awkward shuffling, the unspoken judgment, the eyes that widen then flit the other way. The little girl in me feels exposed by this - They have seen what wasn’t safe to reveal. She wants to run. To bring her baby home, to wrap him up in blankets and hold him close, to tell him he is lovely and beautiful, that nobody knows him like she does. To feel his breath, warm against her cheek as he whispers his favourite scripts to her, to see his smile as she whispers them back. Non-verbal they call him. But what do they know? They will never understand.

Yet I stand my ground, because I know the cost of hiding. All the meaningful relationships I now have were formed through allowing ourselves to be seen as we are, through understanding each other more deeply over time. I want this for my child too. It is okay to want this - Although, that isn’t the message parents always get. There are professional industries that capitalise on the fear around autistic difference, promising to mould and bribe a child into meeting external expectations, promising an easier life. But who is that easier for? When an autistic person continually masks who they are or hides themselves away to make others more comfortable, they are broken by this, becoming ever more isolated and exhausted. In J’s case, I don’t believe he has that option even if he wanted it. His body is often at the edge of his control and sometimes beyond it. He can only move, feel and be as he is.

Compelling autistic people into invisibility, either through masking or through segregation, is also a profound loss to everyone else. There are real friendships never being made. Passions that are never shared. Creativity that is never seen. Damaging assumptions about what it means to be autistic that are never challenged. Narrow conceptions of what it is to be human that are never expanded. We are all diminished by this.

Connecting with someone different to you can feel scary. When someone looks to me to help them interact with J, I’ll be grateful they asked, but I can give no guarantee that their experience will be free from uncertainty and awkwardness. This is no reason not to try. J needs human connection as much as anyone else. It means a lot to him if you achieve that, even for a moment, so this is worth leaving your comfort zone for. As the most well-known advocate of vulnerability says about this, “There is no courage without uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure.” I am sure Brené Brown is right about this, but it must also be acknowledged that the risks she refers to are not the same for everyone.

Parents can worry about taking their children places when they hear, “Of course, everyone’s welcome here, but can you make them be quiet and sit still?” And I’ve heard many autistic adults say they feel a constant message of, “Just be yourself… But not like that!” Those who don’t understand are numerous, and many wilfully so. The risks to an autistic person of being their real self are considerable, for some people in some situations, even dangerous. The onus cannot all be on autistic people to be brave and vulnerable and forever explaining themselves. We need to make the world a safer place for all humans to be who they are, a place where we all present ourselves honestly, where everyone is included, where we all take the time to view each other with openness and kindness.

So, if you’re looking for J and me, you will find us right here, out in the world with everyone else. This life we’re patching together might seem different, but that doesn’t make it ugly. There is no need for you to look away. Like any love when it is real, ours might look imperfect, home-made, improvised. This is its beauty.